The Refugee Republic Project

Subtitle: A Proposed Alternative to Deportation and Indefinite Incarceration

An Imaginative Image of the Refugee Republic under Construction

Introduction

This is not a blueprint. It is a sketch—an imaginative proposal grounded in historical precedent, constitutional principle, and humanitarian urgency. The Refugee Republic is not offered as a turnkey solution, but as a starting point for reimagining how the United States and the world can respond to displacement, incarceration, and exile with vision rather than repression.

The plaque on the Statue of Liberty famously proclaims:

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Yet today, America deports those very masses—often without conviction—into foreign detention centers and prisons. Deporting individuals who have legal permission to reside in the U.S. into indefinite detention under squalid conditions arguably constitutes cruel and unusual punishment, violating the spirit—if not the letter—of the Eighth Amendment (Estelle v. Gamble, 1976; Trop v. Dulles, 1958).

This article proposes an alternative vision: the creation of a Refugee Republic—a self-governing, production-based city-state where displaced individuals, deportees, the homeless, and even domestic parolees can reconstruct their lives. Not a refugee camp. Not a prison. A lawful, rights-based, economically viable and internally governing community. One that, like early America, transforms the unwanted into citizens of purpose and productivity.

The Statue of Liberty in New York City

I. From Deportation to Enslavement: The CECOT Model

Under current policies, deportees are transferred to facilities like El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison, even without formal convictions. President Trump (White House, 2025, as cited in Yahoo News) has praised this model and called for expanded cooperation and prison construction, raising serious concerns about both U.S. constitutional obligations and international human rights.

These transfers are highly performative. Shackled, muscular men are paraded before cameras in a grotesque spectacle of captivity, evoking echoes of slave captures and chain gangs (Rasmussen, 2025). The 13th Amendment permits involuntary servitude only after a criminal conviction. Bypassing due process in these deportations creates not only legal violations but moral ones, and begins to normalize authoritarian practices—among them, the erosion of habeas corpus.

An illustration based on photos of new prisoners at CECOT in El Salvador

More troubling is what such facilities make possible. What might a future autocrat do with 20,000 able-bodied men under control? Nazi Germany’s “Final Solution” began with detention and it is expensive to keep 20,000 or more people in captivity. Russia, in its war on Ukraine, has deployed convicts as “cannon fodder” (Amnesty International, 2024; Harding, 2023; Heller & Yurchuk, 2023). America must not pave the road to its own Holocaust or risk destabilizing neighboring nations through militarized deportation.

II. Historical Models of Removal and Rebirth

A. The Final Solution and Wasted Genius

Before resorting to extermination, the Nazis explored deportation, including a plan to relocate Jews to Madagascar. The plan failed, but it shows a pattern: logistical failure gives way to ideological extremism, and eventually to mass murder and genocide. What was lost wasn’t only life, but untapped brilliance—Einstein and Freud escaped; millions of others did not (Snyder, 2010).

Nazi Holocaust survivors bound for Israel

B. British Penal Colonies

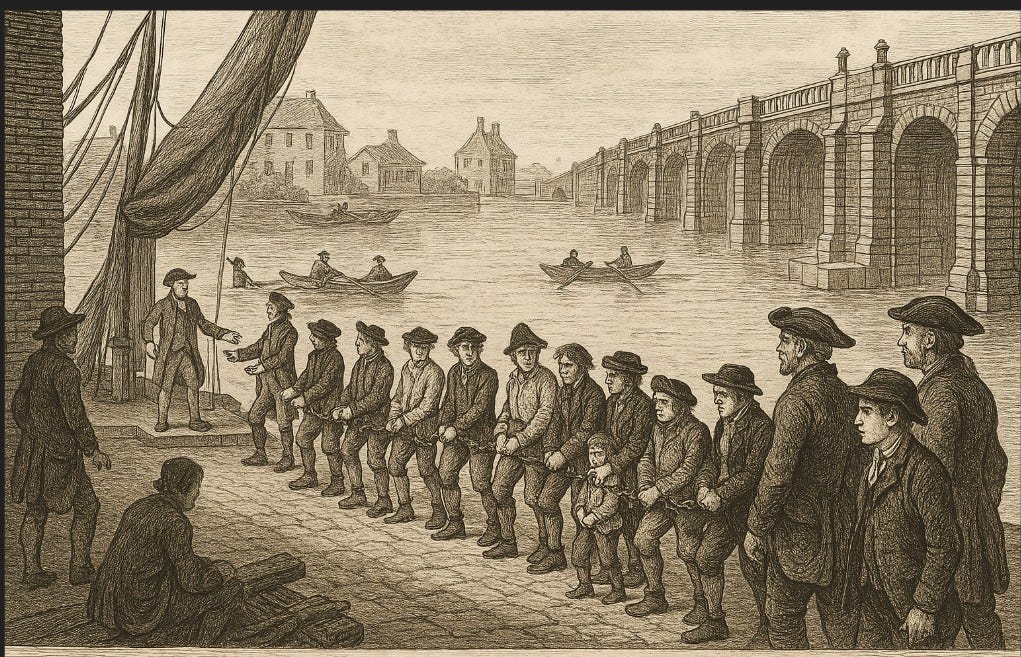

Between the 1600s and 1800s, Britain deported tens of thousands to penal colonies in America and Australia. Offenses ranged from debt to political dissent. Scots captured after Dunbar and Irish rebels under Cromwell were among the coerced labor used to settle these colonies (Erickson, 2014; Anderson, 2018).

British Convicts awaiting Transport to the American Colonies

C. Liberia and the Back-to-Africa Vision

Liberia, founded by formerly enslaved Americans, stands as an early prototype of the Refugee Republic—an intentional, if flawed, nation-building project for the displaced. Its endurance underscores the power of land, governance, and purpose (CIA, 2023; ICTJ, 2006; Adebayo, 2013).

American Methodist Missionaries on their way to Liberia in 1898

III. The Refugee Republic: A New Model

The Refugee Republic would be grounded in a framework of rights and responsibilities, though its precise structure—constitutional, legal, diplomatic—is intentionally left open in this vision to invite expertise, experimentation, and collaboration. Whether chartered through international treaty, bilateral agreement, or Congressional mandate, the concept hinges on the principle that people stripped of status need more than protection: they need a stake in building something new., echoing U.S. constitutional ideals.

Core Features:

Constitutional Protections: Upholding due process and individual liberties.

Visa and Citizenship Tracks: Structured pathways to entry, residency, and citizenship.

Demilitarized Zone: No firearms; peacekeeping under international oversight, with residents of the republic operating their own police force.

Transparent Corrections: Rehabilitation-focused justice.

Productive Infrastructure: Agriculture, digital services, recycling, and fabrication.

Educational Pipeline: Schools, vocational programs, and apprenticeships.

Residents might include deportees, refugees, American citizens—homeless veterans, nonviolent parolees, or prisoners from overcrowded facilities like Rikers Island. With over 1.9 million incarcerated in the U.S. and many prisons condemned for inhumane conditions (Prison Policy Initiative, 2024), a monitored, voluntary transfer to the Refugee Republic could improve outcomes and reduce recidivism. Democratic governance would ensure transparency and civic engagement.

A homeless veteran in the USA

Initially, trained professionals—experts in medicine, governance, law enforcement, psychology, and sociology—would administer the Refugee Republic during its formative phase. As the community stabilized, dedicated residents would be recruited and trained for leadership roles. Some of the trained professionals might decide to become permanent citizens of the Refugee Republic. Over time, democratic elections would be held to select local governance officials, including a president, a congress, and chiefs of public services such as police and fire departments. The goal would be to develop a fully empowered, internally governed civic body capable of managing its own affairs with transparency and legitimacy.

Immigration and Emigration: Initially resembling a UN camp, the Refugee Republic would evolve into a permanent, rights-based municipality. U.S. citizens—including initial staff and medical personnel—would be free to enter and exit. Deportees might be evaluated for future emigration to the host country based on conduct and contribution. Over time, the Republic could grow into a destination of opportunity, much like the U.S. once was—a land where determination and effort created futures.

Refugees in the Darien Gap, Republic of Panama

IV. Cost-Benefit Analysis: From Burden to Investment

The Status Quo (Gulag Economics):

Cost: Over $100/day per detainee; $3+ billion annually (DHS, 2023).

Outcome: International condemnation, radicalization, diminished soft power.

Refugee Republic Model:

Startup: Comparable to building a military base or UN field hospital.

Sustainability: Driven by productivity, aid partnerships, and private investment.

Soft Power: Reshapes global perception of American leadership.

Precedents:

The Panama Canal Zone was U.S.-controlled sovereign territory from 1903 to 1979. Administered by a governor appointed by the President, it housed multiethnic residents—including Black, Chinese, and white Americans—who lived, worked, and were buried there. Though controversial, it demonstrated long-term governance of an autonomous enclave abroad. The author lived and taught in the former Canal Zone from 1982 to 2001 and retired to the interior of Panama until 2012 and thoroughly enjoyed the challenges, experiences and beauty of Panama.

Native American Nations function with semi-sovereign legal systems within the U.S. (DOI, 2024; Wilkins, 2007).

Military Installations governed by the Uniform Code of Military Justice also offer a model for functional jurisdiction outside civilian norms (BBC, 2021).

The Guna Yala of Panama is an Indigenous republic with its own governance and resource rights (Global Forest Coalition, 2015, NDN Collective, 2021).

UNHCR-managed camps already provide health, schooling, and legal systems (Barnett, 2002; Bilkent University, 2021).

Spontaneous Domestic Models:

Las Vegas Storm Drains shelter a subterranean community with its own rules and leadership (Martinez, 2022).

The Freedom Tunnel in New York hosted artists and homeless residents with communal norms (Toth, 2015).

Occupy Wall Street encampments pioneered temporary consensus-based self-governance.

Burning Man, while not a hardship model, proves that a functional, temporary, and law-enforcement-free urban community can exist.

These models demonstrate that order and productivity can emerge from grassroots cooperation—especially when paired with structure and support.

V. Genetic and Sociobiological Considerations

From an evolutionary perspective, genetically diverse populations are better positioned to adapt to change. Recombination enhances immunity, resilience, and phenotypic flexibility (Maynard Smith, 1978; Getahun et al., 2019). The Refugee Republic would bring together survivors—people sifted by conflict, migration, and systemic challenges.

Just as the early United States was shaped by a blend of cultures and lineages, so too would the Republic. Its population might offer not only new cultural forms but biological adaptability suited to an unpredictable future: climate change, novel pathogens, or even human settlement beyond Earth.

VI. Cultural Preparedness: Historical and Imagined Precedents

Throughout history—and literature—we have explored the power of exiles, castaways, and the displaced.

Historical:

Roanoke: A lost colony perhaps absorbed through peaceful integration (Ducros, 2025).

British Penal Colonies: Once marginalized, their populations helped build foundational societies (Anderson, 2018).

Pitcairn Island: Founded by mutineers and their Tahitian companions, functioning across generations (Springer, 2015).

Fictional:

Star Wars: The Rebel Alliance thrives on exile and resistance.

Obi-wan Kenobi of Star Wars

Dune: The Fremen rise from the harsh desert environment to reshape planetary destiny.

Fremen and Frewomen at entrance to their refuge, a Sietch

Les Misérables, Papillon, The Man in the Iron Mask, Oliver Twist: Each depicts transformation under pressure and the human drive for dignity

Dustin Hoffman as Papillion

Oliver Twist having the audacity to ask "Please, sir, I want some more."

VII. A Message to Technocrats and Patriots

To Billionaires: You are already designing cities—Neom, Telosa, smart grids—but often for the elite. Another approach would be to help solve refugee problems and thereby take pressure off established communities in the USA. In essence both approaches are ways of accomplishing the same goals: making life better for people in the USA and preparing for the future. For an example of aspirational urban planning centered on sustainability and access, see Telosa’s vision statement (Telosa, n.d.).

To Americans: This is your Ellis Island moment. Reject cruelty. Embrace opportunity. Redeem our country’s legacy by building the future instead of fearing it. Hope for the USA is, at least in part dependent on hope for the rest of the world.

VIII. Where Could a Refugee Republic Be Situated?

The Refugee Republic could become a national and international asset. Its success would depend on being designed for economic contribution, not containment. It could host factories, research hubs, and service sectors—providing labor, stability, and opportunity to host nations.

Initially, the concept could be presented to the United Nations and willing partners not as a finished product, but as a flexible, negotiable framework. Diplomatic engagement would be key: no nation would be expected to host such a community without seeing mutual benefit—economic, reputational, or geopolitical. To succeed, the Refugee Republic must offer value: as a hub of human capital, resilience, and innovation, rather than a dumping ground for the displaced.. Countries supplying deportees or refugees would be expected to contribute proportionately. Possible locations include:

Overseas zones near existing infrastructure (e.g., near ports or peacekeeping bases).

Underutilized U.S. federal land.

Tribal land, with consent, mirroring casino partnerships that generate revenue and employment.

A domestic version could serve veterans, the unhoused, reentry populations, and asylum seekers. It would offer training, employment, and dignity while reducing burdens on urban systems.

Conclusion: A City on a Hill, Reimagined

Rather than let cruelty define us, the United States can again become a beacon. The Refugee Republic isn’t just a policy proposal—it is a test of our moral imagination.

Will we descend into exile and neglect—or rise through vision and renewal? The worst historical analogies need not become prophecy. This project invites us to choose the better path while we still can.

References

Adebayo, R. I. (2013). Liberia: History and political evolution. International Journal of African History, 16(1), 22–35. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijah/article/view/106682

Amnesty International. (2024). Russia’s use of prisoners in Ukraine conflict. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/01/russia-prisoner-recruitment/

Anderson, C. (Ed.). (2018). A global history of convicts and penal colonies. Bloomsbury Academic. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/58808

Barnett, M. (2002). Eyewitness to a genocide: The United Nations and Rwanda. Cornell University Press.

BBC. (2021). U.S. bases and military jurisdiction abroad. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57693593

Bilkent University. (2021). Functionality of refugee camps. https://yoksis.bilkent.edu.tr/pdf/files/14460.pdf

CIA. (2023). The World Factbook: Liberia. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/liberia/

Department of Homeland Security. (2023). Annual immigration enforcement report. https://www.dhs.gov/publication/immigration-enforcement-statistics-2023

Ducros, H. (2025). Review of Excavating the Lost Colony Mystery by E. Klingelhofer. Southeastern Geographer, 65(1), 119–121. https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.2025.a952577

Erickson, A. (2014). British deportation and transportation policies, 1600–1800. British Archives Journal, 39(2), 55–78.

Getahun, D., Alemneh, T., Akeberegn, D., Getabalew, M., & Zewdie, D. (2019). Importance of hybrid vigor or heterosis for animal breeding. Biochemistry and Biotechnology Research, 7(1), 1–4.

Global Forest Coalition. (2015). Guna Yala and self-governance. https://globalforestcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/panama.pdf

Harding, L. (2023). Russia's convict soldiers in Ukraine. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/01/russia-convict-soldiers-ukraine

Heller, K., & Yurchuk, Y. (2023). Ukraine, Wagner, and Russia’s convict soldiers. Ethics & International Affairs, 37(3), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1017/S089267942300045X

ICTJ. (2006). A brief history of Liberia. https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-Liberia-Brief-History-2006-English.pdf

JHU. (2020). The Panama Canal Zone archive. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/61421

Martinez, M. (2022). Beneath the neon: Life and death in the tunnels of Las Vegas. Las Vegas Underground Press.

Maynard Smith, J. (1978). The evolution of sex. Cambridge University Press.

McCullough, D. (1977). The path between the seas: The creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914. Simon & Schuster.

NDN Collective. (2021). Guna Yala: The islands that won their liberation. https://ndncollective.org/guna-yala-the-islands-that-fought-for-and-won-their-liberation/

Prison Policy Initiative. (2024). Mass incarceration: The whole pie. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2024.html

Rasmussen, D. R. (2025). A return to U.S. slave capture and confinement as political theater. Substack.

SciAm Editors. (2020). The unpredictable value of hybrid populations. Scientific American, 322(4), 66–73.

Snyder, T. (2010). Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

Springer, J. (2015). Pitcairn Island: The legacy of mutiny. Island Studies Journal, 10(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1332301500289

Toth, J. (2015). The mole people: Life in the tunnels beneath New York City. Chicago Review Press.

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2024). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2023. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/global-trends-report-2023

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2024). Native American governance and sovereignty. https://revenuedata.doi.gov/how-revenue-works/native-american-ownership-governance/

Washburn, K. (2006). Federal Indian law and the politics of jurisprudence. American Indian Law Review, 31(2), 619–650. https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol31/iss2/6

White House. (2025). Fact check: Yes, Trump said he wants to deport pro-Hamas immigrants to El Salvador mega-prison. Yahoo News. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.yahoo.com/news/fact-check-yes-trump-said-213200023.html

Telosa. (n.d.). A city built for people, not cars. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://cityoftelosa.com/#vision(https://cityoftelosa.com/#vision)