Abstract

This article calls for the revival of the term Citizen as a unifying, rights-affirming civic identity that transcends inherited divisions of race, ethnicity, and gender. Tracing the historical use of the term in revolutionary America and critiquing modern-day classifications rooted in slavery-era logic, the piece proposes a symbolic act of solidarity: that Americans fill in ethnicity blanks as "Citizen" and adopt "Citizen" as a form of address. It also introduces respectful alternatives for referring to non-citizens, such as "Ally," to ensure dignity and inclusion without diluting the political meaning of citizenship. Further, it presents a brief sociobiological and genetic dismantling of the biological basis of race and confronts White replacement theory using examples drawn from American history and genetics.

Introduction: A House Divided by Categories

In an era in which Americans are divided not only by ideology but by identity boxes (Black, White, Latino, Male, Female, Nonbinary), the call to address one another as Citizen may seem quaint. History suggests otherwise. Use of the term Citizen was once a revolutionary act: a word meant to unify a diverse people around rights, duties, and belonging. To use the term Citizen is to acknowledge the person addressed as a member of "We the People."

Language shapes how we perceive social reality; adopting Citizen as a primary social referent has the potential to shift perception and reduce categorical bias (Whorf, 1956). Gestalt psychology also offers insight: the civic identity of Citizen is greater than the sum of its parts. By integrating ethnicity, gender, and diverse background into one inclusive frame, the term creates a superordinate identity that promotes unity across social lines (Koffka, 1935; Wertheimer, 1924).

Still, the term Citizen need not displace the warm and familiar: of course we call our friends by name, refer to one another as daughters, sons, neighbors, colleagues. Yet, when we engage in civic life—when we speak in courtrooms, sign petitions, vote, march, or deliberate national direction—Citizen is the name that best invokes our constitutional standing and shared responsibility.

Indeed, Citizen is most powerful when used contextually—not universally. In personal contexts, we carry many roles: spouse, parent, friend, worker, artist. But in public and democratic contexts, where rights and responsibilities matter most, Citizen is the address that binds us equally before the law. Just as "Doctor" or "Judge" is used when appropriate to a professional role, Citizen can and should be applied when civic status is central.

This approach preserves the term’s dignity, avoids forced conformity, and restores its rightful place as the linguistic expression of liberty, equality, and mutual obligation. It is not just a form of address; it is a frame for action. It recognizes membership and responsibility in "We the People."

Historical Foundations of Citizen

This strategic use of Citizen has deep roots in the American founding and beyond. Revolutionary leaders used it not casually but consciously, invoking civic identity to unify a fractious population.

In his Address to the People of New York (1788), John Jay begins:

“Consider, my fellow-citizens, what you are about before it is too late…”

Similarly, Thomas Paine in Common Sense (1776) pleads:

“Let the names of Whig and Tory be extinct; and let none other be heard among us, than those of a good citizen…”

Thomas Paine: American Patriot

President Abraham Lincoln, in his 1863 Gettysburg Address, described the United States as “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” President Lyndon B. Johnson, in his 1965 address to Congress advocating the Voting Rights Act, declared, “There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is only an American problem.” John F. Kennedy, in his 1961 inaugural address, implored Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you: ask what you can do for your country.”

These appeals emphasized civic identity over ancestry or status and reflected a republican ideal: that the American people should be united by shared responsibility, not divided by inherited class or caste.

“Citizen” Elevates All Above Gender Discrimination

The civic title Citizen was also central to women’s rights. Susan B. Anthony, after being arrested for voting in 1872, argued that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed her the franchise:

“Being persons, then, women are citizens; and no state has a right to make new classes of citizens… the citizen who has once been clothed with the right to vote cannot be divested of it” (Anthony, 1873).

For Anthony, Citizen was not merely symbolic. It was the legal foundation of equality under the Constitution. Her rhetorical strategy echoes forward today: to be a Citizen is to hold full political standing in the Republic.

To identify first as Citizen short-circuits discrimination under the law and the U.S. Constitution. When our Republic is under strain, when division weakens liberty, there is virtue in choosing unity over distinction. To first identify as Citizen is to foreground rights—and to affirm those rights for others. Of course you have a gender, but in the context of your and others’ rights and responsibilities, Citizen comes first.

“Citizen” Elevates All Above Racial Classification

All ethnicities are eligible for citizenship in the United States. Lingering racial discrimination exists from the past, yet in the current political climate, ethnic classification increasingly serves to divide and disadvantage rather than to redress inequalities.

The infamous “one-drop rule”—holding that any trace of African ancestry made a person legally Black—was not grounded in biology; it was engineered to control citizenship and inheritance (Davis, 1991). Thomas Jefferson, in Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), mused about how many generations of “White blood” were needed to restore a person’s status as White.

His own life complicated the theory. Jefferson likely fathered several children with Sally Hemings, his wife’s half-sister and an enslaved woman. These children were seven-eighths White by ancestry, yet legally enslaved. This example is especially powerful: Jefferson’s stature as a Founder and President could not shield his own children from the racial caste system he helped perpetuate (Gordon-Reed, 2008).

By calling each other Citizen as a term of address between members of We the People, we acknowledge equal constitutional rights and responsibilities.

Reframing Identity: Citizen as a Cognitive and Civic Tool

Social psychology research demonstrates that counter-stereotypical framing can reduce implicit bias over time (Devine et al., 2012). The term Citizen serves as a powerful counter-stereotype. It refocuses perception on constitutional membership and mutual obligation rather than racial or gendered identity.

To say Citizen is to affirm:

The right to vote

The right to speak freely

The right to due process

The duty to protect those rights for all

This language change is not semantic; it is civic practice.

Reject the Checkbox: Ethnicity as “Citizen”

As DEI protections diminish, the collection of ethnic data risks becoming an instrument of exclusion rather than increasing equity. Until safeguards are restored, Americans may resist the logic of identity sorting.

On forms that ask for race or ethnicity, write: Citizen.

This is not denial—it is solidarity. It reclaims the civic ideal of equal standing.

If an Ethnic Box must be filled, write Citizen. Claim the civic ideal of equal standing.

Respectful Terms for Non-Citizens: Ally, Neighbor, Guest

Elevating Citizen must not degrade those who are not yet citizens. There are many dignified alternatives such as:

Ally: for those who stand in solidarity

Neighbor, Guest, or Friend: depending on context

These terms acknowledge moral proximity without erasing legal distinctions. Citizenship entails greater mutual responsibility, but constitutional protections apply to all persons under U.S. jurisdiction.

Again, context is important: Citizen is used when invoking messaging to We the People.

Citizen Deletes Race as a Social Construct

Modern genetics has thoroughly dismantled race as a biological concept. Lewontin (1972) demonstrated that 85% of human genetic variation occurs within so-called racial groups; only a small percentage exists between them.

Organizations such as the American Medical Association now explicitly affirm that race is a social—not biological—construct (AMA, 2019).

Citizen Debunks “White Replacement”

“White replacement theory” imagines that interracial marriage or immigration erodes White lineage. But biologically, this claim is incoherent.

Consider a White farmer who marries a Black woman: their son inherits half the farmer’s DNA. If that son inherits the farm, has the White farmer’s genetic lineage been replaced? No. His son is his biological offspring and carries half his DNA and half of his wife’s DNA.

Racial logic, however, reduces that son to “Black”—as if his White genetic heritage completely vanishes. This is not science; it is a remnant of slave codes. In genetics, lineage persists. In racism, identity is erased—just as it was with Jefferson’s children by Sally Hemings. “White replacement theory” is rooted in slavery laws, slavery labels, and practice—not science.

Would the farmer share more genes in common with his son if he had married a White spouse? Maybe yes, maybe no. He could be more related to a Black wife than to a White one. Recall Jefferson and Hemings: If an all-White cousin of Jefferson married a Black child of Jefferson and Hemings, they could be closely related. Why might this matter? To a geneticist concerned with how closely a father is related to his biological son, the father’s direct contribution of genes to his son is generally about half. If, however, the father is genetically related to his wife, then he could be more closely related to his son if some of his wife’s genes are his own by virtue of shared ancestry. Of course, if husband and wife are too closely related, problems can occur, such as unmasking of deleterious recessive genes (Dawkins, 2004).

This issue is deeply and profoundly personal for many Americans. Sons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters, are stripped of their father’s and mother’s equal contributions to their genetic identity, and a label, based on the logic of slavery, is applied instead.

In Summary

Citizen is a useful and potentially powerful way of noting to others that they are included in the group of “We the People” and accorded all rights, privileges, and responsibilities for membership in that group. The time is right to reactivate the solidarity implied in this patriotic form of address.

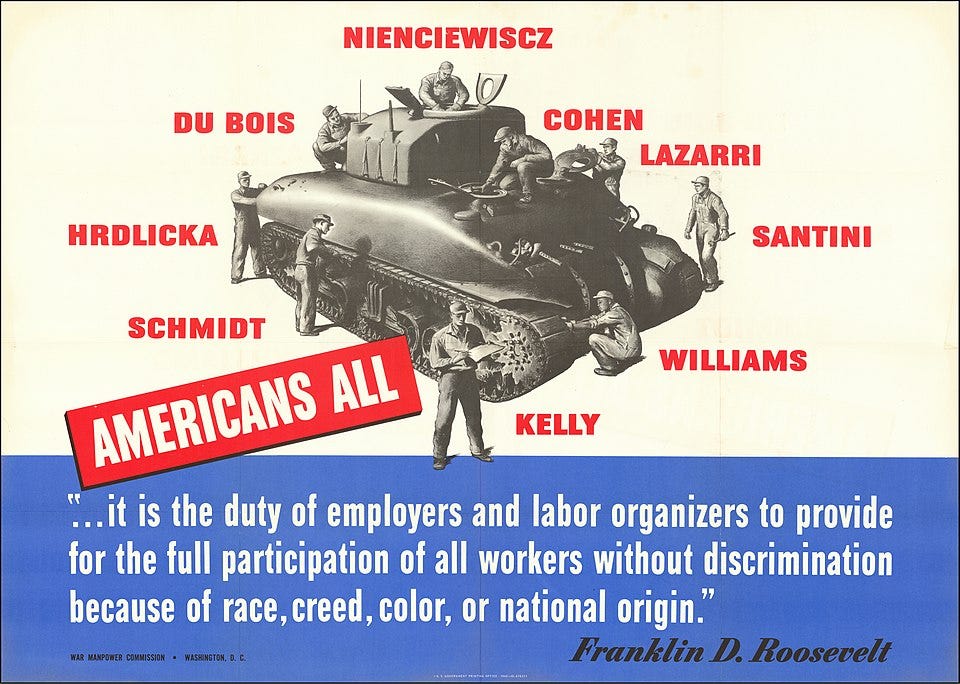

A poster produced in 1942 when there may have been discrimination against fellow Americans with, for example, German and Italian surnames.

References

American Medical Association. (2019, November 19). New AMA policies recognize race as a social, not biological, construct. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/ama-press-releases/new-ama-policies-recognize-race-social-not-biological-construct

Anthony, S. B. (1873). Is it a crime for a U.S. citizen to vote?

https://susanbanthonyhouse.org

Dawkins, R. (2004). The ancestor’s tale: A pilgrimage to the dawn of evolution. Houghton Mifflin.

Davis, F. J. (1991). Who is Black?: One nation’s definition. Penn State University Press.

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003

Gates, H. L., Jr. (1997). Thirteen ways of looking at a Black man. Random House.

Gordon-Reed, A. (2008). The Hemingses of Monticello: An American family. W. W. Norton & Company.

Jay, J. (1788/2000). Address to the People of New York. In B. Bailyn (Ed.), The debate on the Constitution: Part one (pp. 702–708). Library of America.

Jefferson, T. (1785). Notes on the State of Virginia. John Stockdale.

Johnson, L. B. (1965, March 15). Special message to Congress: The American promise.

Kennedy, J. F. (1961, January 20). Inaugural address.

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt psychology. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Lewontin, R. C. (1972). The apportionment of human diversity. In T. Dobzhansky, M. K. Hecht, & W. C. Steere (Eds.), Evolutionary biology (Vol. 6, pp. 381–398). Springer.

Lincoln, A. (1863, November 19). The Gettysburg Address.

National Archives. (n.d.). Founding documents of the United States. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs

Paine, T. (1776). Common sense. W. and T. Bradford.

Wertheimer, M. (1924). Gestalt theory. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A source book of Gestalt psychology (1938, pp. 1–11). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf (J. B. Carroll, Ed.). MIT Press.